This month I visited Fort Spokane, a former U.S. military base that is located where the Columbia and Spokane rivers join. Today those waters are dammed in what is now the Lake Roosevelt National Scenic Area. The fort was built in 1880 to keep “the peace” between white settlers and Indian residents on the Colville Reservation. (Click on each photo to see larger pictures on separate picture pages.)

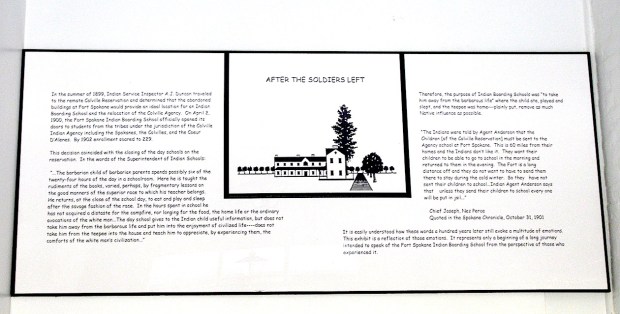

The National Park Service notes, “In many ways, the Indian experience at Fort Spokane is a microcosm of the Indian experience across the United States.” In 1900 the fort become an Indian boarding school, one of the most controversial legacies of the treatment of American Indians. Children were forcibly moved here from their families from the Colville and Spokane reservations, leading to major protests by Indian leaders, including Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce. The school was then closed in 1908. (See the display from the visitor center below.)

Click on the picture of a display at the Fort Spokane Visitors Center entrance to read the description about the Indian boarding school controversy surrounding the boarding of more than 200 American Indian children here at the start of the 20th century.

Spokane Historical, published by Eastern Washington University, describes this controversial era, which was followed by having the fort become a tuberculosis sanitarium after 1909: “The idea behind Indian Boarding Schools was that the children would benefit from learning skills that would help them integrate into the white population. It was the general consensus among the white government agencies, at the time that this was far superior to the education that they would have received at home. As Capt. Richard H. Pratt said on the education of Native Americans, the cruel philosophy was, ‘Kill the Indian, and Save the Man.'”

After much of the fort was removed prior to 1930, a few remaining buildings were saved, such as those captured in my photographs and incorporated into a cultural site to be administered in the area surrounding the newly created reservoir that filled the river canyon after the Columbia River was dammed in Coulee City. I highly recommend anyone traveling to eastern Washington visit to the fort and lake and enjoy the beautiful scenery (I heard coyotes when I camped there). Also take the time to learn about the area’s history. This location truly is a microcosm of the state’s development in the last two centuries.